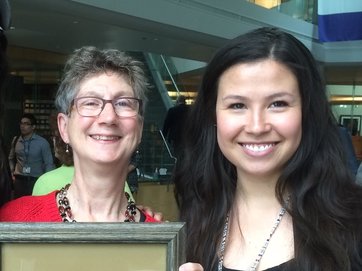

Partner Profile: Jackie Siegel and Angela Young, Indigenous Languages and Education Secretariat2/23/2018  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the thirteenth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Angela Young and Jackie Siegel are roommates, colleagues in the Indigenous Languages and Education Secretariat, and, now, co-representatives for the Secretariat on the NWT On The Land Collaborative (though they assured me that they don’t actually spend that much time together). The two even share a job title, Co-ordinator, although they have different backgrounds and responsibilities within the division. Angela, a “recovering teacher,” supports the delivery of Indigenous culture and language programming in schools through curriculum development and training; Jackie, who has a background in public health, supports monitoring and evaluation initiatives. Both Jackie and Angela are relatively new to Yellowknife. Jackie was drawn north from his hometown of Vancouver by a job with the Department of Education, Culture, and Employment (ECE). He only intended to stay a year. Three years later, he is still here with no intention of leaving. If you’ve attended any events organized by NWT Pride, then you’ve likely crossed paths with Jackie. He served as the organization’s President for two years. As with many new arrivals to the North, Jackie has expanded his repertoire of outdoor activities since relocating to Yellowknife: “I picked up canoeing since moving here. I’ve given up car camping for canoe camping, which has been exciting!” His goal for this winter is put his new cross country skis to use. Angela, who also hails from British Columbia, moved to Yellowknife in 2015 after 13 years in Inuvik. For a decade, she was an English teacher at Samuel Hearne/East Three Secondary. She also spent two years working as the Literacy Coordinator for the Beaufort Delta Educational Council. Leaving the Delta was bittersweet. In addition to the relationships she developed with students and community members while in Inuvik, Angela formed a strong bond with the land through time spent at camps throughout the Delta. Ultimately, it was the vision and purpose of the Assistant Deputy Minister for Education and Culture that drew her to Yellowknife. For Rita Mueller, work at ECE headquarters is another way of serving and supporting the territory’s schools, students, and communities. One of the things she loves about her new community are the many wonderful yoga studios and instructors. Angela and Jackie’s worlds collided in 2015 with the creation of the Indigenous Languages and Education Secretariat (at that time known as the Aboriginal Languages Secretariat). ILES (pronounced “isles”) is tasked with “support[ing] the preservation, promotion, and revitalization of Indigenous languages throughout the NWT.” It is a misconception that the Secretariat, which is housed in ECE, is primarily concerned with supporting language learning in schools. To the contrary, almost half of ILES funding is funnelled through Indigenous governments and non-profits to support grassroots language initiatives. Increasingly, Indigenous language education programs are taking place on the land, a reflection, Angela observes, of the deep connections between Indigenous languages and the land: “Most Indigenous people would say that the language comes from the land, so language teachers, language champions, and Elders always advocate for learning on the land. An immersion camp is the gold standard for a language experience.” Members of the Secretariat have been following the Collaborative since it was created in 2015. Existing funding arrangements, however, prevented the division’s participation. A newly minted agreement with the federal Department of Heritage has changed this; as of fall 2017, ILES is officially a funding partner of the NWT On The Land Collaborative. For the Secretariat, the Collaborative, while still relatively new, is attractive because it “has a system in place.” By taking advantage of this existing structure, ILES is able to ensure that a greater percentage of their funds are directed towards programming rather than administration. Of particular value are the Community Advisors, who, in addition to being an invaluable support for prospective applicants, are the eyes and ears of the Collaborative in their regions. As Angela notes, “The Community Advisors are a unique and invaluable aspect of the Collaborative, offering funding partners a window onto the programs and activities that are happening in their region.” Equally attractive to ILES are the relationships that the Collaborative has built and strengthened over the last three years with a diverse collection of organizations and programs across the territory. Not only will tapping into this network give the Secretariat a better understanding of the language revitalization components of land-based programming, but it will also allow ILES to extend their reach and diversify the recipients of their support. The Collaborative, for its part, is happy to have representatives from Education, Culture, and Employment at the table, especially given the number of applications received over the last two years from schools. In 2016, the Collaborative applications were submitted by 38 of the territory’s 49 schools. This year, almost a third of the grant requests came from educational institutions. The Collaborative and grant recipients will benefit from the expertise that Jackie, Angela, and their colleagues bring to the table. Successful grant recipients will have access to ILES staff, including linguists, evaluators, and curriculum specialists. With the participation of the Secretariat in the Collaborative, more land-based projects with language revitalization as a primary focus will be supported. Jackie and Angela are also hopeful that the involvement of ILES will encourage more programs to make language revitalization a core component of their activities. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like the Indigenous Languages and Education Secretariat (ILES) to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).

2 Comments

The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the twelfth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Tracey Williams arrived to our meeting with a flat square mason jar labelled, “Yellowknife Homegrown Herbal.” “A little goes a long way,” she remarked about the tea, with a smile and her signature laugh. It is just like Tracey to share a little something from her garden. Anyone who has spent time with the animated expat knows she is passionate about food and food security, but especially food security in Indigenous communities. Food, she believes, “is a lifeline to the land, culture, and healing,” a means through which Indigenous communities can “regain what has been lost to the traumas of the colonization process.” In addition to being an avid gardener and advocate, Tracey is the new face of TNC Canada in the territory; she was hired as the Northern Conservation Lead in late February. TNC Canada (not to be confused with the Nature Conservancy of Canada, which is a separate though kindred organization) is the Canadian affiliate of the world’s largest conservation organization, The Nature Conservancy. TNC Canada, as Tracey explains, is much more than a conservation organization, however: “We are interested in supporting sustainable communities, where people and nature are connected, and we are building the future around that connection.” TNC Canada has had a presence in the North for almost a decade. Initially, the organization provided technical support to the NWT Protected Areas Strategy, a community-based approach to conservation planning aimed at creating a network of protected areas across the territory. Much of TNC Canada’s focus in the intervening years has centred on supporting Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation in the creation of the Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve (Thaidene Nëné means “land of our ancestors” in Dënesųłiné). TNC Canada has also provided support to the community’s Ni Hat’ni Dene program. Ni Hati’ni, which means “watchers of the land,” is an Indigenous Guardian program modelled on the Haida Watchmen. Tracey’s task in the coming weeks and months will be to expand TNC Canada’s role in the territory. TNC Canada has been involved with the Collaborative since the early days. Tracey’s predecessor attended the initial meetings in 2014 and TNC Canada was one of the first organizations to sign on as a funding partner. Like other partners, TNC Canada was attracted to the Collaborative because it meets an important need in the territory. As Tracey notes, “On the land programming, in all of the communities in the Northwest Territories, is something everyone wants to be doing. It’s something that everyone wants to be happening in their communities.” And so it made sense for TNC Canada to get involved with an initiative committed to removing barriers to spending time on the land. TNC Canada’s support for land-based programming and their participation in the Collaborative was one of the things that drew Tracey to the organization: “Since moving to the NWT 15 years ago, everything I’ve done has had an on the land focus. That’s been my lens. I really like the fact that TNC Canada is not just supporting a land trust initiative, they want to support people, their place in nature, and their connection to the land.” Tracey believes strongly that on the land programs are “vital to defining a pathway to sustainability for the future of the Northwest Territories.” Tracey, who hails from the Chicago area, first came north to paddle. (She and her partner, Steve, have at various points travelled the Back, Kazan, Coppermine, and Thelon Rivers.) It wasn’t long before Tracey made the move permanently, relocating from Sante Fe, New Mexico, where she had been working in land restoration and watershed management, to Łutsël K’é, where she took a job coordinating a traditional knowledge project on East Arm fisheries. In the ensuing twelve years, Tracey became an important part of the community fabric, involved in everything from the community garden and school board to environmental assessment interventions and community radio. In 2013, Tracey, Steve, and their three kids relocated to Yellowknife. It was while living in Łutsël K’e that Tracey began her apprenticeship as a moosehide tanner under the tutelage of a trusted and respected local Elder, whom Tracey is now fortunate to call a friend: “I started out as her lackey. I was there to carry water or start fires or attend to the smokehouse, whatever needed to be done. Over time I realized I really liked hide tanning.” With the arrival of twins in 2011, Tracey’s time for tanning dramatically decreased. She makes a point, however, of returning to Łutsël K’é every June for a hide tanning camp to work on one of her in-progress hides. (Side note: the Łutsël K’é Women’s Group’s Annual Hide Tanning Camp is one of 35 grant recipients for 2017). Other members of the Collaborative see the positive outcomes of land-based programming in terms of the wellbeing of participants or of the health of the land. Tracey brings a new perspective to the table: “Dene people, Inuit people, Indigenous people all have foodways.” Tracey recognizes the importance of those foodways to Indigenous identity, wellbeing, and sovereignty, hence why she thinks supporting the continuance of those foodways through the Collaborative is so important. As with other outcomes, food security doesn’t need to be an explicit objective of land-based programs to support Indigenous foodways and food sovereignty: “If you have an on the land project, inevitably, you will have a duck, a goose, a caribou head, a moose, a trout, whatever is in season, over the fire. You may go berry picking. In this way, on the land programming naturally supports food security regardless of whether or not we acknowledge it.” The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like TNC Canada to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the eleventh in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. John B. Zoe describes his current responsibilities as a Senior Advisor to the Tłı̨chǫ Ndek’àowo (Tłı̨chǫ Government) in this way: “I go to lend support to keep things moving. Sometimes people need to be reminded of their strengths and responsibilities.” John B. uses the same mentorship skills in his role as the Community Advisor for the Tłı̨chǫ region with the NWT On The Land Collaborative. Community Advisors are appointed by Indigenous governments in each region to serve as their representative to the Collaborative. They are available to applicants throughout the process, while also assisting in the annual selection of grant recipients. As valuable as John B.’s mentorship skills are to the Collaborative are his experiences developing and supporting land-based programs in the Tłı̨chǫ. He has played a pivotal role in the creation and ongoing success of Wha Dǫ Ehtǫ K’è (Trails of Our Ancestors), an annual canoe trip that keeps Tłı̨chǫ history and culture alive by retracing traditional routes. In the early 1990s, John B. spent his summers travelling through Tłı̨chǫ territory with Elders, including the late Harry Simpson, and archaeologist Tom Andrews: “We were gathering stories, but there was no one to share them with. We didn’t see our own people travelling these rivers. So we began organizing canoe trips for youth so they could travel with the Elders and hear the stories.” The first Trails trip ran in 1995. Over the course of 15 days, five 22-foot canoes paddled from John B.’s home community of Behchokǫ̀ to Gamètì, arriving in time for the Tłı̨chǫ Annual Gathering. This summer marks the 23rd anniversary of the program. In mid-July, flotillas of canoes from each of the four Tłı̨chǫ communities will set out for the Gathering, which is scheduled to take place in Behchokǫ̀. Wha Dǫ Ehtǫ K’è has not only continued, it has prospered, John B. shares: “Each year, we receive more applications than we have seats in the canoes!” To understand the cultural importance of these canoe trips, you have to know something about the importance of stories for the Tłı̨chǫ. Stories contain knowledge about how to be Tłı̨chǫ and live in respectful relation to the land. Stories are not disembodied; they are tied to specific places. John B., borrowing from Elder Harry Simpson, likens the landscape to a book: “The pages are your travels.” To understand the book’s teachings, in other words, you need to be on the land, hearing the stories in the places that they belong. A recent history of Wha Dǫ Ehtǫ K’è captures it best: “By travelling traditional trails, which link places like beads on a string, Tłı̨chǫ youth are told stories as each place is visited.” The Trails trips, like land-based programs more generally, are about looking back in order to move forward. By returning to older ways of doing things, in this case travelling by canoe in community and hearing the stories, the hope is that youth will be grounded in the Tłı̨chǫ way of life and able to chart a way forward for themselves as individuals and as a people. If Tłı̨chǫ youth are to “be strong like two people,” a vision first articulated by Chief Jimmy Bruneau, but which is best known in the words of Elizabeth Mackenzie, they need this education on the land alongside Elders and community leaders. While participants experience the canoe trips in their own way as individuals, ultimately Wha Dǫ Ehtǫ K’è is about collective experience and collective knowledge. John B. explains it this way: “If somebody from this group of 100 canoeists learns something it will stay with them and when it’s time to fill the gap, they will fill that gap. The more people that have these bits and pieces of information, they become an army of knowledgeable people about our collective story.” It’s hard to ignore the parallels with the Collaborative and the value that each individual member through their knowledge and experiences brings to the collective. While the Community Advisors share certain responsibilities, they all approach their role in different ways, depending on their personalities and the needs of their region. For John B., being a Community Advisor is about reminding Tłı̨chǫ people and communities of their strengths and abilities, not the least of which is the knowledge of the land, the animals, relationships, and governance: “Our communities have this knowledge, held by our professors and they seek to pass on this information.” Land-based programs that engage Elders are vital to this work of reviving the old ways and ensuring continued stability for the future. More than once during our conversation, John B., in reference to the Tłı̨chǫ, noted, “Our work is to acknowledge what was there before and use it as a basis for application in a modern way.” One example of this meeting of old and new is the Reviving Trails Project, which seeks to revitalize ancient Tłı̨chǫ canoe routes. Most recently, an 18-person group, which included John B., travelled the Mowhi Trail by canoe from Behchokǫ̀ to the barrenlands and back to Wekweètì, plotting their route and important cultural places with GPS. Not only did the trip improve the conditions of the trails and result in a digital map of the route, making it easier for future travellers, but it also enabled the sharing of stories about the places visited along the way and generated new experiences for younger Tłı̨chǫ on their territory. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Tłı̨chǫ Ndek’àowo (Tłı̨chǫ Government) to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the tenth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Ask any member of the NWT On The Land Collaborative about Sarah True, the Collaborative Administrator, and invariably they will tell you about her binders and spreadsheets. Sarah is an organizational wizard. Her management of the application process and her facility with Microsoft Excel has made the grantmaking cycle infinitely easier for the partners over the last two years. Sarah’s passion for organization goes beyond columns and tabs. She also played a pivotal role in arranging last year’s very successful learning trip. In case you’re getting the wrong impression of Sarah, she has a good sense of humour and is lots of fun. According to her business cards, Sarah is the Regional Environmental Assessment Coordinator for the North Slave office of the Government of the Northwest Territories’ department of Environment and Natural Resources (ENR). For the last year or so, however, Sarah has been on secondment to ENR headquarters, where she has been working on a number of projects, namely developing traditional economy and country foods strategies, updating the government’s traditional knowledge policy, and developing an action plan for the same, all while managing the affairs of the Collaborative. Sarah was first employed by ENR as a summer student, coordinating fire ecology camps in the South Slave. In 2006, she returned to the department, working first as a Regional Planner and later, as the Regional Environmental Assessment Coordinator for the South Slave. Two years later, she relocated to the North Slave office in Yellowknife. In addition to positions with ENR, Sarah has worked with the NWT Métis Association, helping to develop environmental education materials for children; the South Slave Research Institute (ARI) as a research assistant ; and NWT Fire and Parks Canada as a radio operator and fire clerk. (Sarah was able to put both her GIS skills and her fire experience to work during the notorious 2014 fire season.) As her resume makes clear, Sarah is a jack of all trades. She is also a lifelong learner. She has four diplomas in Integrated Resource Management; Wildlife, Fisheries, Grasslands, and Recreation; Forestry; and Management Studies. Today, Sarah is at work on a Bachelor of Arts in Sustainable Business Practices. In 2015, Sarah was approached by Fred Mandeville and Erin Kelly, at that time the Superintendent of the North Slave Region and Assistant Deputy Minister of ENR respectively, about working with the Collaborative. The request came at just the right time; Sarah, who clearly has an appetite for variety, had been looking for new experiences in her professional life. Not to mention, she has a personal passion for land-based programs (more on that in a moment). Sarah joined the NWT On The Land Collaborative at the beginning of the pilot year. She played a central role in establishing the administrative materials and systems that have guided the Collaborative over the last two years. Sarah’s position as the Collaborative Administrator is unique amongst the partners. She describes herself as a “middle person,” providing support in different ways to applicants, grant recipients, funders, and community advisors. Sarah believes strongly in the Collaborative’s mission to get people out on the land, but particularly its commitment to supporting community-based initiatives: “It’s not one thing that we’re trying to give to everyone. It is communities telling us what they need, whether it’s resources, financial support, advice.” Beyond making it easier for people to spend time on the land in the way that they want through the provision of funds and resources, Sarah values the way that the Collaborative has helped to make connections between funders and projects, between different regions and communities, and, in some cases, between individuals and organizations within a single community. Growing up in Fort Smith, Sarah spent significant amounts of time on the land, surrounded by a large extended Cree and Métis family. Sarah’s eldest (she is a mum to three) had a very similar childhood, often spending weeks at a time at their cabin with family, learning to hunt, trap, and fish. Today he is confident and at home in the bush, a trait that Sarah attributes to this early education. Sarah is impressed with the variety and creativity of approaches to land-based programming exhibited by grant recipients, but she has a soft spot for projects that promote intergenerational knowledge transfer: “I’d really like to see more opportunities for younger kids and for family units. Take kids out with their parents and their grandparents. I think that’s a dynamic that means more to people.” While she and her family spend less time on the land since moving to Yellowknife, they continue to enjoy camping, ice fishing, hiking, and canoeing. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Environment and Natural Resources to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  Debbie Delancey and Kyla Kakfwi-Scott Debbie Delancey and Kyla Kakfwi-Scott The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the ninth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Kyla Kakfwi-Scott of Health and Social Services has the ideal slate of experiences for the NWT On The Land Collaborative. As Dechinta’s inaugural Program Director she helped to shepherd the fledgling bush university from concept paper to program delivery, so she knows the demanding cycle of applying for funding and reporting, while also trying to deliver meaningful programming. Kyla has also sat on the other side of the table as a funder: managing Ekati Diamond Mine’s community investment and Aboriginal engagement program; serving on the board of the NWT chapter of the United Way; advising the Small Change Fund; and chairing the selection committee for the Arctic Inspiration Prize. Perhaps most importantly, through her time at Dechinta and more recently through her involvement with Dene Nahjo, an NWT-based Indigenous leadership collective, Kyla has experienced the transformative power of being on the land and seen the same in others. It’s no wonder that Kyla was handpicked by Deputy Minister of Health and Social Services, Debbie Delancy, to coordinate the Collaborative, a role she shares with Steve Ellis of Tides Canada. Kyla joined the department in May 2013, shortly after Paul Andrew, Chair of the Minister’s Forum on Addictions and Community Wellness, released the Forum’s final report, Healing Voices. The Forum, which was convened in November 2012 to hear directly from NWT residents about how best to address addictions and promote community wellness, travelled to 21 communities over four months: “What the Forum heard more than anything else during its travels is the land heals…So strong is this belief, with so many examples of its success, that the Forum is making on-the-land programming its number one recommendation.” The Forum’s findings were re-iterated in the weeks and months that followed at anti-poverty workshops, at gatherings of community representatives, and in meetings between the Minister of Health and Social Services and Indigenous governments. The people spoke and Health and Social Services listened, devoting 1 million dollars that year to supporting land-based healing programs. It was not an insignificant amount of money. However, given the expense of on the land programs and the demand, it was inadequate in meeting community needs, so the department was looking for ways to leverage other funding. If you read Steve Ellis’s profile, you will recall the serendipitous meeting that happened between the Northern Lead for Tides Canada and the Deputy Minister in 2014 and the November 2014 meeting on funding collaboratives the two organizations co-hosted to “stimulate thinking on the art of the possible,” as Debbie describes it. Of particular interest to the Deputy Minister was the Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Collaborative, a collaborative with a provincial government at the table, which could serve as a model for a NWT-based initiative. (Engaging in these kinds of projects can be tricky for governments because of the legislative and policy frameworks that regulate the spending of public monies.) It was at that meeting that Health and Social Services officially committed to starting a collaborative fund to support land-based programs in the territory. The collaborative model appealed for a number of reasons beyond attracting additional dollars. By offering a mechanism for government departments supporting land-based programs to talk to one another about the work they are doing, a collaborative could help to break down government silos. Likewise, a collaborative had the potential to facilitate connections within and between communities, all with the aim of “combining strengths and combining resources,” in Debbie’s words. While there was much that was attractive about the models presented at the workshop, it has been important to both women that what was to become the NWT On The Land Collaborative reflect local priorities and ways of working. For this reason, from the beginning, community representatives have been at the table. Kyla explains, “The people who are actually applying for funding and running the programs have had a really important voice in both articulating the need for a collaborative approach to funding, but also what that approach should look like.” Through dialogue between the partners, which consist of community advisors and funders, the Collaborative will continue to evolve: “It’s not just about developing a process that will then be set in stone…It’s about continuous improvement, how we are working, how we might work differently, and how that changes over time.” To date, both women are happy with the progress that has been made. Kyla notes, “We started with a giant leap of faith on the part of all of the partners and so our first critical measure of success is coming out of the first round, we’ve maintained all of the existing partner relationships... and we’ve brought in a couple of new partners.” Debbie adds, “It’s been very positive the engagement that we’ve had from communities and Indigenous governments. The ability to get government departments involved, as well as NGOs and industry and to get everyone to agree. We didn’t really have a lot of templates in Canada for that, so that it has been successful has been very exciting.” While much of our interview time was taken up with discussing the history and mechanics of the Collaborative, both Kyla and Debbie have personal reasons for wanting to support land-based programming in the NWT. Debbie, who is originally from upstate New York, lived for eight years with her partner in his home community of Fort Good Hope, during which time she spent extended periods of time on the land: “I had the opportunity to experience the power of the land and to see the impact that spending time in touch with the land had on people…The land is the most powerful tool that we have to support healing at a community and individual level.” Kyla’s response to the same question hints at the variations and complexities in the relationships that people have to the land in the NWT and also the importance of land-based programs for Indigenous youth: “My own personal connection to land has been one of needing to find it having grown up [in Yellowknife] rather than in either of the places that I would consider myself to be from…I’m trying to learn by doing and creating opportunities for myself and other people to be around that.” The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Health & Social Services to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the fourth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Jess Dunkin’s resume is an interesting mix of two different kinds of experience: outdoor education and academia. She has instructor-level certifications in canoeing and first aid and a PhD in Canadian history. She has taught history and gender studies at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa and led canoe trips in the shield country of Northern Ontario. She has written articles for Pathways: the Ontario Journal of Outdoor Education and Histoire Social/Social History. The one thing that ties these two lives together is Jess’s love of the outdoors. Both have been valuable in her current position as Director of On the Land Programs at the NWT Recreation and Parks Association (NWTRPA) and as the NWTRPA’s representative on the NWT On The Land Collaborative. Jess has always had a special relationship to the outdoors. She grew up on a farm in Eastern Ontario and spent part of every summer at camp and her grandparents’ cottage: “I know that I need to be outside…It’s a place where I feel more connected to myself, I feel more connected to the world around me, and I feel more connected to the people I’m with.” It was this love of the outdoors that led Jess to pursue work in outdoor education while in high school, first as a camp counsellor and later leading canoe trips. She continued to work at summer camps and outdoor centres while in university and at Teacher’s College. A love of history led her to graduate school in 2007, where she channeled her passion for the outdoors into her research, writing about girls’ summer camps and canoeing. In 2014, Jess was wrapping up a postdoctoral fellowship at Queen’s University and looking for a next step. The academic job market was dire and there were few other opportunities for her in Ottawa. Jess had already been thinking about moving North, when she heard about the On the Land Programs Consultant position at the NWTRPA: “While I was in grad school I basically stopped paddling, I wasn’t really doing trips, I let my certifications lapse. I kind of thought I had left that life behind…When I started talking to Geoff [the NWTRPA’s Executive Director] about the job, I found myself circling back… and I was excited about that prospect.” Even before relocating to Yellowknife, Jess understood that there were very real differences between the outdoor education that had been her bread and butter down south and the on the land programs that she would be supporting in the North: “To me, land-based programs are about revitalizing the deep connections between Indigenous people, their territories, and traditional knowledges/practices targeted by colonialism. Land-based programs heal people and communities and the territories they call home and ultimately, they nurture self-determination and the restoration of traditional forms of governance.” Jess is keenly aware of being a non-Indigenous settler from the south in her position: “I have struggled to figure out how to do this work in a good way. I was really fortunate to be able to attend a Dechinta short course last spring and to be able to think through in a really practical way my responsibilities and my job, but it’s a process. I’m not there yet.” In 2014, the NWTRPA was invited to be part of the collaborative funding workshop that was the precursor to the NWT On The Land Collaborative. ED Geoff Ray went on behalf of the organization: “(At this meeting) the Tides Foundation, Nature Conservancy, Health & Social Services, and others each stood up in the room and made contributions of tens of thousands, in some cases hundreds of thousands of dollars. We didn’t have money to offer, but we had a pile of experience and expertise in training and relationships to communities and organizations that do on the land programs. We offered to contribute those resources, relationships, and connections.” That experience and those relationships come from a decade of delivering and supporting on the land programs in the NWT. Between 2007 and 2010, the NWTRPA organized the Mackenzie Youth Leadership Trip. The organization took a number of learnings from that experience, particularly around programming planning, training, and risk management, and has shared them with communities looking to offer similar programs. Geoff believes, “One of the strengths of the Collaborative is that you have a handful or more organizations who are coming from different backgrounds and mandates. You’ve government, non-government, and corporate interests coming together to support community-based programs. There are lots of different outcomes that people are working towards but I think it’s really exciting that you can have this diverse group of people working together in such a transformative way.” Working as the NWTRPA’s representative on the Collaborative has allowed Jess to put her diverse skills to work. When the NWTRPA first became a partner in the Collaborative in early 2016 that meant lending expertise in training. As time has gone by the NWTRPA has taken on additional roles assisting with information sharing and communications. These days, the Collaborative keeps Jess busy writing copy for the website, managing the social media accounts, and writing editorial content, such as partner profiles. For Jess, along with everything else, being part of the Collaborative has been an invaluable learning experience: “It has exposed me to lots of other people and programs that I otherwise wouldn’t have known about. It has also just been really inspiring to hear about the amazing land-based programming happening in the territory on both a large and a small scale.” Jess says that she’s still not always comfortable in her position, but the Collaborative has provided a space where she can work in a good way, guided by strong Indigenous leadership and local expertise. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like the NWT Recreation and Parks Association to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the seventh in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Nicole McDonald is unabashedly passionate about collaboratives: “I love collaborative funding models!” In addition to making it easier for recipients to access funds, Nicole has seen firsthand how collaboratives can support projects that need a little extra help: “One of the things I found while working with the Saskatoon Collaborative Funding Partnership was that we could see groups doing good work, but they weren’t successful in their funding applications because they weren’t good at writing proposals.” To address this, the Partnership hosted workshops for prospective grantees on proposal writing and budget development. Almost immediately, they saw improvements in the quality of applications being submitted. Nicole, who is currently the Program Director for Indigenous Initiatives at the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation, has become something of an expert in collaboratives. At present, she is working with a variety of partners on a number of funding collaboratives which include: {Re}conciliation and the Arts; the Indigenous Innovation Demonstration Fund; and now, the NWT On the Land Collaborative. Collaboratives, Nicole believes, promote diversity by bringing different partners to the table and allow for a more efficient use of resources through shared administration. They can also serve as a gateway for people and organizations who might not have traditionally supported certain kinds of initiatives: “With the close of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we are seeing a growing number of organizations that want to fund Indigenous communities, but don’t know how to or where.” Enter initiatives like the NWT On The Land Collaborative: “Organizations are able to contribute as little or as much as they want, both in terms of financial resources and level of engagement with the Collaborative. Because there are other partners already sitting at the table, funding is automatically leveraged. Also, the governance structure is already in place to ensure that funding is going directly to communities, and the adjudication process is done in collaboration by community members and the partners.” If done right, it is low risk and high reward. The trajectory of the McConnell Foundation’s involvement in the NWT On The Land Collaborative is a case in point. When the opportunity to be involved as a partner in piloting the Collaborative, “it was kind of a no brainer,” Nicole admits. “Because it was a pilot, the initial level of funding was relatively low, so it wasn’t a huge risk.” More importantly, if it succeeded, it would have a significant impact. All the better that it fit nicely with one of the Foundation’s emerging priorities, reconciliation: “One of the ways in which we get at reconciliation is through reculturalization and being on the land is a huge part of that.” For her part, Nicole appreciates the flexibility of the collaborative funding model. Participants can be involved as much or as little as they want, something that appeals to her, given her current position. As the Program Director for Indigenous Initiatives, Nicole manages the McConnell Reconciliation Initiative, which currently has three priority areas: increasing the number of organizations and networks active in the reconciliation space; fostering innovative platforms for change; and supporting the use of social innovation and solutions finance tools in our Indigenous initiatives: “Right now, the McConnell Foundation has a large Indigenous portfolio with limited staffing. There are a lot of initiatives that we want to be supporting, so having the flexibility to have other partners step up and work with communities more directly is a bonus.” That the Foundation feels comfortable stepping back a little reflects the fact that they “trust the partners sitting at the table.” Though Nicole has been working with funding collaboratives for approximately 10 years, she is relatively new to the world of philanthropy. Prior to joining the McConnell Foundation in 2015, she worked in the public service. She had a hand in implementing the Common Experience Payment as part of the Indian Residential School Resolution; she worked on programming and policy with the Urban Aboriginal Strategy; and she was involved in community safety planning as part of the Government of Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Initiative. Nicole is Métis from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and has spent most of her life living on Treaty 6 Territory. In 2012, Nicole relocated from the prairies to Ottawa so that she could pursue new work opportunities. She never expected to work for a philanthropic organization, but she is glad that the opportunity presented itself: “It’s been the best two years!” For Nicole, there is no separation between her work life and her home life. Both she and her husband work in the Indigenous space and their five children are very involved as well. Her three sons are active in the Moosehide Campaign, a grassroots initiative working to address violence against women and girls. Inspired by a meeting with Cindy Blackstock, her daughters started a letter-writing campaign asking the Prime Minister to accept the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal 2016 ruling which found that the Government of Canada is discriminating against First Nations children living on-reserve. Her eldest son is a member of the Steering Committee for 4Rs, a youth movement committed to creating spaces for cross-cultural dialogue with an eye to transforming the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. All of this in addition to a busy schedule of swimming, soccer, hockey and synchronized swimming. One of their family traditions is to head back to Saskatchewan in the summer to spend time together on the land visiting with family, swimming, fishing, hiking and berry picking. Last summer they also had the opportunity to visit with Elder Maria Campbell at her traditional family’s homestead at Gabriel’s Crossing in Batoche. Nicole notes, “Being back home and on the land is important to our family as it helps to remind us of our identity, history, values and connection to mother earth.” The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like J.W. McConnell Family Foundation to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the fifth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. In 2014, Steve Ellis, the recently appointed Northern Lead for Tides Canada, found himself with a bit of money for an on the land camp in the Dehcho. He quickly realized the money wouldn't go very far. At the same time, he was aware that his was not the only organization supporting land-based programs in the NWT, so Steve arranged a meeting with Debbie Delancey, Deputy Minister for Health and Social Services. At the time, her department was piloting land-based programs for wellness purposes. The gist of that meeting, to borrow from Steve, was: "I have some money, you have some money, there are other organizations supporting on the land programs. Maybe we should look at figuring out some way of pooling our resources and making our money work better for us and for the people doing this work on the ground." Debbie agreed. In the weeks that followed, Steve and Debbie reached out to Erin Kelly of Environment and Natural Resources, Kyla Kakfwi-Scott of Health and Social Services, and Rebecca Plotner of Dominion Diamond. The group envisioned a system in which a wide range of organizations could pool their resources, attract additional funding, reduce the administrative burden of people delivering land-based programs, and, most importantly, “empower Northerners to set priorities for how the pooled money should work.” Steve’s employer, Tides Canada, is a philanthropic organization that connects donors and doers to in the pursuit of “a healthy environment, social equity, and economic prosperity for all Canadians.” In recent years, they have put more of their energy into nurturing collaborative funds for just these reasons. A gathering of government, industry, NGOs, and philanthropic organizations later that year to learn more about collaborative funding models from those with experience in Manitoba, British Columbia, and Australia brought the idea one step closer to reality. In the fall of 2015, the NWT On The Land Collaborative was officially launched. In its first year, the Collaborative distributed $480,000 to 35 projects across the territory. At the outset, Steve’s self-described role was that of “catalyst or instigator, depending on your point of view.” He not only initiated the conversation with Debbie, but he and Tides Canada were integral to organizing the November 2014 gathering. As the Collaborative has developed a momentum of its own, Steve has been able to focus more on the responsibilities of a funding partner—securing funds from his organization and participating in the annual review and approval of applications—though he continues to play an important role attracting philanthropic foundations to the Collaborative and he does other administrative work besides. Tides Canada hosts some of the dollars that are part of the Collaborative’s funding pot. They also provide web space and communications support. Steve grew up in Winnipeg. It was while completing a Masters in Environmental Studies at Waterloo that he came north for the first time, to Łutsel K’e, a Denesoline community on the East Arm of Tu Nedhe (Great Slave Lake). Though he didn’t know it at the time, he and his wife Tracey would spend the better part of 15 years living in the community and raising a family. During that time, Steve worked for the Łutsel K’e Dene First Nation and other First Nations in the NWT and BC. Amongst other things, he delivered land-based programs: “I’ve been around long enough to have seen young people fifteen years later who have gone through these types of programs and who attribute change in their lives to these types of programs, so I am definitely a believer in these types of programs.” In 2013, Steve, Tracey, and their three kids moved to Yellowknife and Steve joined Tides Canada. Tides Canada, like Steve, sees on the land programs as vital to ensuring community wellbeing in the North: “Colonialism and trauma is largely responsible for the social issues in many Northern communities. Recovery from the harms of colonialism is about reclaiming what has been lost. On the land programs are great at rebuilding those relationships with community, culture, and the land.” For all of his experience with land-based programs, Steve too has benefitted from his involvement with the Collaborative: “We support a wide range of projects from the classic ‘community moves entire families out into the bush for a long time’ to urban disadvantaged youth spending an afternoon eating traditional food over a fire in a campground. We’re not in a position to judge what is more impactful. It’s depends on where people are and what their circumstances are. One thing I’ve learned through my participation in the Collaborative is that what an on the land program can be can be very, very different, but the outcomes are generally the same.” There is no doubt that the Collaborative had a successful first year. Funders, community advisors, and grant recipients have all been happy with the process. The only complaint is that the need far exceeds the current budget, so Steve’s goal over the coming months is to engage new donors and to encourage existing partners to devote more of their resources to the fund: “Most of the donors are still in the ‘let’s see where this goes’ mindset and I think it will be that way for a few years, but we would like to get to the point where people are comfortable enough with the collaborative approach that larger and larger amounts of the resources they have allocated for on the land programming can be run through the Collaborative.” Steve’s larger ambition is to make the Collaborative indispensable to land-based programming in the NWT. “We’ve wanted to be a one-stop shop and we are a one-stop shop, but I think becoming THE one-stop would be great.” In other words, the Collaborative would become the place to go for learning about innovative programs, best practices, and accessing tools to help with program delivery, as well as funding and resources. Steve also sees potential for the Collaborative to serve as a model for similar initiatives in the other territories. Steve, like other members of the Collaborative, enjoys spending time on the land himself. His Instagram feed of late has documented a hiking trip with Tracey and the kids to Utah and regular trips out to the family’s fish net on Yellowknife bay. Come summer, you are most likely to find the Ellis-Williams clan cruising around Tu Nedhe in a motor boat, with a requisite stop in Łutsel K’e, Steve’s first home in the North and one of the many places he has seen firsthand the value of land-based programming. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Tides Canada to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the fourth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Rebecca Plotner’s enthusiasm for the Collaborative is infectious: “I really think [the Collaborative] is wonderful…Everyone who is working on it is really great with many good ideas…And the programs being supported are awesome!” And she should know. Rebecca, who works for the Dominion Diamond Corporation, has been involved with the Collaborative since it was little more than an idea. She recalls early meetings with Kyla Kakfwi-Scott (GNWT Health and Social Services) and Steve Ellis (Tides Canada), two of the driving forces behind the Collaborative: “It started off with three or four of us hanging around a table talking about it, throwing out different ideas, and figuring out how we could get it expanded.” Even at that early stage, Rebecca saw the potential of bringing together diverse partners from government, industry, and the non-profit sector to pool their resources and support land-based programs in the territory: “We looked to examples in the south like the Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Fund. They started out with a small amount of money, but it keeps growing and they are able to help out so many people now.” Rebecca is equally impressed with how far the NWT On The Land Collaborative Fund has come in such a short period of time: “Seeing where it started to having our first workshop to where we are today in just over two years. It has been great to see the interest [in the Collaborative] and how much people have wanted to support it. The distance we covered in that time is huge!” Rebecca’s employer shares her enthusiasm for the Collaborative—they recently doubled their investment in the fund. In their words, Dominion Diamond is “pleased to be able to contribute to an initiative such as this, which emphasizes collaboration and partnership, enabling projects to come to a single place for funding. We believe the NWT On The Land Collaborative will be a key resource in the sustainability of on the land projects in the North.” Rebecca is a member of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation. Although born in Illinois, she was raised in Dettah by her parents Sarah (nee Charlo) and Mark Plotner. Her grandparents are Judy (nee Betsina) Charlo the late Joe Charlo. After studying Biochemistry at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, Rebecca returned to Yellowknife. In 2010, Rebecca was hired as a Community Relations Advisor Trainee with BHP Billiton. She was attracted to the people-oriented nature of the position (“I love talking and working with people!”) and the prospect of seeing more of the territory (“I grew up in the North, but I had never been to a community that you can’t drive to.”). Six-and-a-half years later, Rebecca is a Community Development Advisor with Dominion Diamond, which acquired BHP’s interests in 2013. Dominion operates the Ekati Diamond Mine, located on Lac de Gras approximately 300 kilometres northeast of Yellowknife. Amongst other things, Rebecca helps to administer the Ekati Plus Community Development Program. Through this program Dominion Diamond provides financial and in-kind support to innovative initiatives that have a long-lasting impact on the people and communities of the North, including on the land programs: “At the Ekati mine, we have long recognized the importance of on the land activities, Traditional Knowledge (TK), and providing opportunities for young people and other community members to learn from their Elders and each other.” The mining corporation’s funding priorities include traditional knowledge activities, youth education, literacy initiatives, and healthy lifestyles. Land-based programs have the potential to satisfy all of these objectives. Rebecca, for her part, values programs that support children and youth spending time on the land. Growing up in Dettah, Rebecca spent a lot of time outside: swimming at the docks, fishing on the big lake, and visiting her family’s cabin. Her mom was raised on the land in Wool Bay and she made it a priority to pass along her experiences and values to her kids: “We’ve always had that connection to the land and respect for the land. It’s always been a part of my life.” One of Rebecca’s favourite things now is to spend time at her family cabin, which is a 1.5 hour boat ride and 5km hike from Yellowknife. When she looks around Dettah today, she sees children and youth spending more time in the community and inside: “They’re not running around on the ice or going fishing on the back lakes as much. So, for me, it’s great to see programs that encourage them to get out on the land and connect them with our culture.” When asked about the future of the Collaborative, Rebecca responded without hesitation, “I know it’s going to expand…I’m really looking forward to seeing how far it goes…and the type of impact that it’s going to have in the North. It’s going to be great.” The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Dominion Diamond to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and funding decisions. This is the third in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Carolyn DuBois, The Gordon Foundation’s representative on the Collaborative, is Toronto born and raised, but that doesn’t mean she’s out of place in the out of doors: “I love canoe tripping! Everyone is always surprised by this, maybe because I live in the city, but canoeing is my favourite!” Summers at Glen Bernard Camp and a high school semester at Outward Bound fostered this passion for paddling. These experiences also set her on career path that would see her focus on the human dimensions of water-related environmental issues. Following an undergraduate degree in Biology from Mount Allison, Carolyn packed her bags and headed for Barcelona where she completed a Masters in Environmental Management at the Autonomous University. Her research explored conflict between artisanal and industrial fisheries in Africa.. Today, Carolyn is the Water Program Manager at The Gordon Foundation, a philanthropic organization based in Toronto that seeks to amplify Northern voices and promote collaborative stewardship of freshwater resources. Amongst other things, Carolyn is responsible for the recently launched Mackenzie DataStream, an open access platform for sharing water data in the Mackenzie Basin. Mackenzie DataStream was built in close partnership with the government of the Northwest Territories. The project, which brings together information produced by community monitoring programs throughout the Basin, enables evidence-based water policy. As part of this project, Carolyn spent a few days on the Deh Cho (Mackenzie River) last year: “For much of my time at the Foundation, I’ve been managing the Mackenzie program, so to actually be on the river was really special.” The trip was also an opportunity to get to know the people and communities with whom she had been working for four years in a really different way: “Before this, I had spent a lot of time on the phone with people from Toronto. It’s very different to be out on the water with people, but also to have that time around the fire to really get to know people.” Learning trips are also an important part of how the Collaborative operates (learn more about our first learning trip here). The Gordon Foundation (previously the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation) is a new partner for the 2017 grant cycle. Founded in 1965, the Foundation is an operational charity, which is to say that they deliver their own programs, including the Jane Glassco Northern Fellowship, a policy and leadership development program for Northern youth. (Jane Glassco Fellow Kyla Kakfwi-Scott has been instrumental in the evolution of the Collaborative.) That said, the Foundation maintains an interest in supporting grassroots initiatives that further their mission. The Collaborative provides an opportunity for the Foundation to do just that, by connecting them with meaningful community-driven land-based projects in the NWT. The value of land-based programs for Northern communities is self-evident to the Foundation’s President and CEO Sherry Campbell. Since assuming that role early in 2016, Sherry has travelled extensively in the NWT and Nunavut. Regardless of the community or the issue being discussed—mental health, cultural revitalization, residential schools, sustainability—Sherry has observed that land-based programs are always part of generating solutions that promote community wellness: “We keep hearing over and over how important on the land programming is and we need to pay attention to that.” Before joining The Gordon Foundation, Sherry was the president of Frontier College, a national non-profit literacy organization. That experience made her sensitive to the onerous cycle of funding applications and reporting: “The capacity to write good applications and good reports can be a barrier…I saw solid community-led projects that were important to the community that were not getting funded because of the complexity of application processes. What I really love about [the Collaborative] is that it removes these barriers and focuses on getting good, community-led work done.” Sherry sees important lessons in the funding model adopted by the Collaborative. For example, she values the fact that the Collaborative provides more to communities and projects than funds. She also appreciates the Collaborative’s emphasis on providing continued support to projects that work: “Funders always want new and innovative projects, but if you really want to make change in communities, you also have to invest in and maintain what is working.” Of particular note is the Collaborative’s commitment to community-directed programming: “I like the fact that [the Collaborative] just gets out of the way. You give [communities] support, you help them get them what they need, and then you give them the funds that lets them do what they are good at doing.” The Collaborative, in other words, is supportive, but not meddlesome. Sherry attributes this approach to the people at the table, many of whom are community leaders themselves and thus are respectful of local goals and expertise. The Collaborative also benefits from having southern partners like The Gordon Foundation, who brings a network of foundations and organizations to the table and also a capacity to translate northern experiences for southern audiences. Carolyn, as the Foundation’s representative on the Collaborative, is enthusiastic about this new responsibility: “I’m really looking forward to seeing the breadth of work that people are doing and also the ideas that people are developing to address issues in their particular place.” She has seen firsthand how land-based programs are opportunities for learning, growth, and fostering well-being and she looks forward to finding ways to help NWT communities continue to offer such programs. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like The Gordon Foundation to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]). |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed