The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the tenth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Ask any member of the NWT On The Land Collaborative about Sarah True, the Collaborative Administrator, and invariably they will tell you about her binders and spreadsheets. Sarah is an organizational wizard. Her management of the application process and her facility with Microsoft Excel has made the grantmaking cycle infinitely easier for the partners over the last two years. Sarah’s passion for organization goes beyond columns and tabs. She also played a pivotal role in arranging last year’s very successful learning trip. In case you’re getting the wrong impression of Sarah, she has a good sense of humour and is lots of fun. According to her business cards, Sarah is the Regional Environmental Assessment Coordinator for the North Slave office of the Government of the Northwest Territories’ department of Environment and Natural Resources (ENR). For the last year or so, however, Sarah has been on secondment to ENR headquarters, where she has been working on a number of projects, namely developing traditional economy and country foods strategies, updating the government’s traditional knowledge policy, and developing an action plan for the same, all while managing the affairs of the Collaborative. Sarah was first employed by ENR as a summer student, coordinating fire ecology camps in the South Slave. In 2006, she returned to the department, working first as a Regional Planner and later, as the Regional Environmental Assessment Coordinator for the South Slave. Two years later, she relocated to the North Slave office in Yellowknife. In addition to positions with ENR, Sarah has worked with the NWT Métis Association, helping to develop environmental education materials for children; the South Slave Research Institute (ARI) as a research assistant ; and NWT Fire and Parks Canada as a radio operator and fire clerk. (Sarah was able to put both her GIS skills and her fire experience to work during the notorious 2014 fire season.) As her resume makes clear, Sarah is a jack of all trades. She is also a lifelong learner. She has four diplomas in Integrated Resource Management; Wildlife, Fisheries, Grasslands, and Recreation; Forestry; and Management Studies. Today, Sarah is at work on a Bachelor of Arts in Sustainable Business Practices. In 2015, Sarah was approached by Fred Mandeville and Erin Kelly, at that time the Superintendent of the North Slave Region and Assistant Deputy Minister of ENR respectively, about working with the Collaborative. The request came at just the right time; Sarah, who clearly has an appetite for variety, had been looking for new experiences in her professional life. Not to mention, she has a personal passion for land-based programs (more on that in a moment). Sarah joined the NWT On The Land Collaborative at the beginning of the pilot year. She played a central role in establishing the administrative materials and systems that have guided the Collaborative over the last two years. Sarah’s position as the Collaborative Administrator is unique amongst the partners. She describes herself as a “middle person,” providing support in different ways to applicants, grant recipients, funders, and community advisors. Sarah believes strongly in the Collaborative’s mission to get people out on the land, but particularly its commitment to supporting community-based initiatives: “It’s not one thing that we’re trying to give to everyone. It is communities telling us what they need, whether it’s resources, financial support, advice.” Beyond making it easier for people to spend time on the land in the way that they want through the provision of funds and resources, Sarah values the way that the Collaborative has helped to make connections between funders and projects, between different regions and communities, and, in some cases, between individuals and organizations within a single community. Growing up in Fort Smith, Sarah spent significant amounts of time on the land, surrounded by a large extended Cree and Métis family. Sarah’s eldest (she is a mum to three) had a very similar childhood, often spending weeks at a time at their cabin with family, learning to hunt, trap, and fish. Today he is confident and at home in the bush, a trait that Sarah attributes to this early education. Sarah is impressed with the variety and creativity of approaches to land-based programming exhibited by grant recipients, but she has a soft spot for projects that promote intergenerational knowledge transfer: “I’d really like to see more opportunities for younger kids and for family units. Take kids out with their parents and their grandparents. I think that’s a dynamic that means more to people.” While she and her family spend less time on the land since moving to Yellowknife, they continue to enjoy camping, ice fishing, hiking, and canoeing. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Environment and Natural Resources to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).

1 Comment

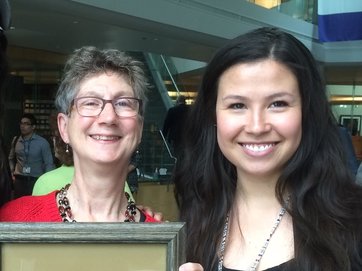

Debbie Delancey and Kyla Kakfwi-Scott Debbie Delancey and Kyla Kakfwi-Scott The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the ninth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Kyla Kakfwi-Scott of Health and Social Services has the ideal slate of experiences for the NWT On The Land Collaborative. As Dechinta’s inaugural Program Director she helped to shepherd the fledgling bush university from concept paper to program delivery, so she knows the demanding cycle of applying for funding and reporting, while also trying to deliver meaningful programming. Kyla has also sat on the other side of the table as a funder: managing Ekati Diamond Mine’s community investment and Aboriginal engagement program; serving on the board of the NWT chapter of the United Way; advising the Small Change Fund; and chairing the selection committee for the Arctic Inspiration Prize. Perhaps most importantly, through her time at Dechinta and more recently through her involvement with Dene Nahjo, an NWT-based Indigenous leadership collective, Kyla has experienced the transformative power of being on the land and seen the same in others. It’s no wonder that Kyla was handpicked by Deputy Minister of Health and Social Services, Debbie Delancy, to coordinate the Collaborative, a role she shares with Steve Ellis of Tides Canada. Kyla joined the department in May 2013, shortly after Paul Andrew, Chair of the Minister’s Forum on Addictions and Community Wellness, released the Forum’s final report, Healing Voices. The Forum, which was convened in November 2012 to hear directly from NWT residents about how best to address addictions and promote community wellness, travelled to 21 communities over four months: “What the Forum heard more than anything else during its travels is the land heals…So strong is this belief, with so many examples of its success, that the Forum is making on-the-land programming its number one recommendation.” The Forum’s findings were re-iterated in the weeks and months that followed at anti-poverty workshops, at gatherings of community representatives, and in meetings between the Minister of Health and Social Services and Indigenous governments. The people spoke and Health and Social Services listened, devoting 1 million dollars that year to supporting land-based healing programs. It was not an insignificant amount of money. However, given the expense of on the land programs and the demand, it was inadequate in meeting community needs, so the department was looking for ways to leverage other funding. If you read Steve Ellis’s profile, you will recall the serendipitous meeting that happened between the Northern Lead for Tides Canada and the Deputy Minister in 2014 and the November 2014 meeting on funding collaboratives the two organizations co-hosted to “stimulate thinking on the art of the possible,” as Debbie describes it. Of particular interest to the Deputy Minister was the Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Collaborative, a collaborative with a provincial government at the table, which could serve as a model for a NWT-based initiative. (Engaging in these kinds of projects can be tricky for governments because of the legislative and policy frameworks that regulate the spending of public monies.) It was at that meeting that Health and Social Services officially committed to starting a collaborative fund to support land-based programs in the territory. The collaborative model appealed for a number of reasons beyond attracting additional dollars. By offering a mechanism for government departments supporting land-based programs to talk to one another about the work they are doing, a collaborative could help to break down government silos. Likewise, a collaborative had the potential to facilitate connections within and between communities, all with the aim of “combining strengths and combining resources,” in Debbie’s words. While there was much that was attractive about the models presented at the workshop, it has been important to both women that what was to become the NWT On The Land Collaborative reflect local priorities and ways of working. For this reason, from the beginning, community representatives have been at the table. Kyla explains, “The people who are actually applying for funding and running the programs have had a really important voice in both articulating the need for a collaborative approach to funding, but also what that approach should look like.” Through dialogue between the partners, which consist of community advisors and funders, the Collaborative will continue to evolve: “It’s not just about developing a process that will then be set in stone…It’s about continuous improvement, how we are working, how we might work differently, and how that changes over time.” To date, both women are happy with the progress that has been made. Kyla notes, “We started with a giant leap of faith on the part of all of the partners and so our first critical measure of success is coming out of the first round, we’ve maintained all of the existing partner relationships... and we’ve brought in a couple of new partners.” Debbie adds, “It’s been very positive the engagement that we’ve had from communities and Indigenous governments. The ability to get government departments involved, as well as NGOs and industry and to get everyone to agree. We didn’t really have a lot of templates in Canada for that, so that it has been successful has been very exciting.” While much of our interview time was taken up with discussing the history and mechanics of the Collaborative, both Kyla and Debbie have personal reasons for wanting to support land-based programming in the NWT. Debbie, who is originally from upstate New York, lived for eight years with her partner in his home community of Fort Good Hope, during which time she spent extended periods of time on the land: “I had the opportunity to experience the power of the land and to see the impact that spending time in touch with the land had on people…The land is the most powerful tool that we have to support healing at a community and individual level.” Kyla’s response to the same question hints at the variations and complexities in the relationships that people have to the land in the NWT and also the importance of land-based programs for Indigenous youth: “My own personal connection to land has been one of needing to find it having grown up [in Yellowknife] rather than in either of the places that I would consider myself to be from…I’m trying to learn by doing and creating opportunities for myself and other people to be around that.” The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Health & Social Services to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the fourth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Jess Dunkin’s resume is an interesting mix of two different kinds of experience: outdoor education and academia. She has instructor-level certifications in canoeing and first aid and a PhD in Canadian history. She has taught history and gender studies at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa and led canoe trips in the shield country of Northern Ontario. She has written articles for Pathways: the Ontario Journal of Outdoor Education and Histoire Social/Social History. The one thing that ties these two lives together is Jess’s love of the outdoors. Both have been valuable in her current position as Director of On the Land Programs at the NWT Recreation and Parks Association (NWTRPA) and as the NWTRPA’s representative on the NWT On The Land Collaborative. Jess has always had a special relationship to the outdoors. She grew up on a farm in Eastern Ontario and spent part of every summer at camp and her grandparents’ cottage: “I know that I need to be outside…It’s a place where I feel more connected to myself, I feel more connected to the world around me, and I feel more connected to the people I’m with.” It was this love of the outdoors that led Jess to pursue work in outdoor education while in high school, first as a camp counsellor and later leading canoe trips. She continued to work at summer camps and outdoor centres while in university and at Teacher’s College. A love of history led her to graduate school in 2007, where she channeled her passion for the outdoors into her research, writing about girls’ summer camps and canoeing. In 2014, Jess was wrapping up a postdoctoral fellowship at Queen’s University and looking for a next step. The academic job market was dire and there were few other opportunities for her in Ottawa. Jess had already been thinking about moving North, when she heard about the On the Land Programs Consultant position at the NWTRPA: “While I was in grad school I basically stopped paddling, I wasn’t really doing trips, I let my certifications lapse. I kind of thought I had left that life behind…When I started talking to Geoff [the NWTRPA’s Executive Director] about the job, I found myself circling back… and I was excited about that prospect.” Even before relocating to Yellowknife, Jess understood that there were very real differences between the outdoor education that had been her bread and butter down south and the on the land programs that she would be supporting in the North: “To me, land-based programs are about revitalizing the deep connections between Indigenous people, their territories, and traditional knowledges/practices targeted by colonialism. Land-based programs heal people and communities and the territories they call home and ultimately, they nurture self-determination and the restoration of traditional forms of governance.” Jess is keenly aware of being a non-Indigenous settler from the south in her position: “I have struggled to figure out how to do this work in a good way. I was really fortunate to be able to attend a Dechinta short course last spring and to be able to think through in a really practical way my responsibilities and my job, but it’s a process. I’m not there yet.” In 2014, the NWTRPA was invited to be part of the collaborative funding workshop that was the precursor to the NWT On The Land Collaborative. ED Geoff Ray went on behalf of the organization: “(At this meeting) the Tides Foundation, Nature Conservancy, Health & Social Services, and others each stood up in the room and made contributions of tens of thousands, in some cases hundreds of thousands of dollars. We didn’t have money to offer, but we had a pile of experience and expertise in training and relationships to communities and organizations that do on the land programs. We offered to contribute those resources, relationships, and connections.” That experience and those relationships come from a decade of delivering and supporting on the land programs in the NWT. Between 2007 and 2010, the NWTRPA organized the Mackenzie Youth Leadership Trip. The organization took a number of learnings from that experience, particularly around programming planning, training, and risk management, and has shared them with communities looking to offer similar programs. Geoff believes, “One of the strengths of the Collaborative is that you have a handful or more organizations who are coming from different backgrounds and mandates. You’ve government, non-government, and corporate interests coming together to support community-based programs. There are lots of different outcomes that people are working towards but I think it’s really exciting that you can have this diverse group of people working together in such a transformative way.” Working as the NWTRPA’s representative on the Collaborative has allowed Jess to put her diverse skills to work. When the NWTRPA first became a partner in the Collaborative in early 2016 that meant lending expertise in training. As time has gone by the NWTRPA has taken on additional roles assisting with information sharing and communications. These days, the Collaborative keeps Jess busy writing copy for the website, managing the social media accounts, and writing editorial content, such as partner profiles. For Jess, along with everything else, being part of the Collaborative has been an invaluable learning experience: “It has exposed me to lots of other people and programs that I otherwise wouldn’t have known about. It has also just been really inspiring to hear about the amazing land-based programming happening in the territory on both a large and a small scale.” Jess says that she’s still not always comfortable in her position, but the Collaborative has provided a space where she can work in a good way, guided by strong Indigenous leadership and local expertise. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like the NWT Recreation and Parks Association to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the seventh in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Nicole McDonald is unabashedly passionate about collaboratives: “I love collaborative funding models!” In addition to making it easier for recipients to access funds, Nicole has seen firsthand how collaboratives can support projects that need a little extra help: “One of the things I found while working with the Saskatoon Collaborative Funding Partnership was that we could see groups doing good work, but they weren’t successful in their funding applications because they weren’t good at writing proposals.” To address this, the Partnership hosted workshops for prospective grantees on proposal writing and budget development. Almost immediately, they saw improvements in the quality of applications being submitted. Nicole, who is currently the Program Director for Indigenous Initiatives at the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation, has become something of an expert in collaboratives. At present, she is working with a variety of partners on a number of funding collaboratives which include: {Re}conciliation and the Arts; the Indigenous Innovation Demonstration Fund; and now, the NWT On the Land Collaborative. Collaboratives, Nicole believes, promote diversity by bringing different partners to the table and allow for a more efficient use of resources through shared administration. They can also serve as a gateway for people and organizations who might not have traditionally supported certain kinds of initiatives: “With the close of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we are seeing a growing number of organizations that want to fund Indigenous communities, but don’t know how to or where.” Enter initiatives like the NWT On The Land Collaborative: “Organizations are able to contribute as little or as much as they want, both in terms of financial resources and level of engagement with the Collaborative. Because there are other partners already sitting at the table, funding is automatically leveraged. Also, the governance structure is already in place to ensure that funding is going directly to communities, and the adjudication process is done in collaboration by community members and the partners.” If done right, it is low risk and high reward. The trajectory of the McConnell Foundation’s involvement in the NWT On The Land Collaborative is a case in point. When the opportunity to be involved as a partner in piloting the Collaborative, “it was kind of a no brainer,” Nicole admits. “Because it was a pilot, the initial level of funding was relatively low, so it wasn’t a huge risk.” More importantly, if it succeeded, it would have a significant impact. All the better that it fit nicely with one of the Foundation’s emerging priorities, reconciliation: “One of the ways in which we get at reconciliation is through reculturalization and being on the land is a huge part of that.” For her part, Nicole appreciates the flexibility of the collaborative funding model. Participants can be involved as much or as little as they want, something that appeals to her, given her current position. As the Program Director for Indigenous Initiatives, Nicole manages the McConnell Reconciliation Initiative, which currently has three priority areas: increasing the number of organizations and networks active in the reconciliation space; fostering innovative platforms for change; and supporting the use of social innovation and solutions finance tools in our Indigenous initiatives: “Right now, the McConnell Foundation has a large Indigenous portfolio with limited staffing. There are a lot of initiatives that we want to be supporting, so having the flexibility to have other partners step up and work with communities more directly is a bonus.” That the Foundation feels comfortable stepping back a little reflects the fact that they “trust the partners sitting at the table.” Though Nicole has been working with funding collaboratives for approximately 10 years, she is relatively new to the world of philanthropy. Prior to joining the McConnell Foundation in 2015, she worked in the public service. She had a hand in implementing the Common Experience Payment as part of the Indian Residential School Resolution; she worked on programming and policy with the Urban Aboriginal Strategy; and she was involved in community safety planning as part of the Government of Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Initiative. Nicole is Métis from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and has spent most of her life living on Treaty 6 Territory. In 2012, Nicole relocated from the prairies to Ottawa so that she could pursue new work opportunities. She never expected to work for a philanthropic organization, but she is glad that the opportunity presented itself: “It’s been the best two years!” For Nicole, there is no separation between her work life and her home life. Both she and her husband work in the Indigenous space and their five children are very involved as well. Her three sons are active in the Moosehide Campaign, a grassroots initiative working to address violence against women and girls. Inspired by a meeting with Cindy Blackstock, her daughters started a letter-writing campaign asking the Prime Minister to accept the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal 2016 ruling which found that the Government of Canada is discriminating against First Nations children living on-reserve. Her eldest son is a member of the Steering Committee for 4Rs, a youth movement committed to creating spaces for cross-cultural dialogue with an eye to transforming the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. All of this in addition to a busy schedule of swimming, soccer, hockey and synchronized swimming. One of their family traditions is to head back to Saskatchewan in the summer to spend time together on the land visiting with family, swimming, fishing, hiking and berry picking. Last summer they also had the opportunity to visit with Elder Maria Campbell at her traditional family’s homestead at Gabriel’s Crossing in Batoche. Nicole notes, “Being back home and on the land is important to our family as it helps to remind us of our identity, history, values and connection to mother earth.” The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like J.W. McConnell Family Foundation to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  On the land programs promote community, family, and individual wellbeing, and are vital to healthy ecosystems and economies. This year, the NWT On The Land Collaborative will distribute $634,845 to 35 projects across the territory that connect NWT residents with their land, culture, and community. This is the second year that the Collaborative has been administering grants to on the land programs in the NWT. Coincidentally, the Collaborative also supported 35 projects in 2016. However, the average grant has risen by 62% to just over $18,000: “Although we are supporting the same number of projects this year, we have been able to fully fund more projects, which means that they don’t have to go elsewhere for funds to make their programs happen,” shares Steve Ellis of Tides Canada, one of the driving forces behind the Collaborative. As the funding pot grows, the Collaborative is better able to meet its mandate of making it easier and less time consuming for people to access funds for land-based programs. Grants range from $3000 to support a canoe trip for grade nine students in Fort Smith to $60,000 for healing and wellness camps for youth in Rádeyįlįkóé (Fort Good Hope). Other funded projects include Trails on the Land, a 10-day trip beginning in Tuktoyaktuk that will take youth and elders through the traditional hunting territory of their ancestors; a land-based youth mentorship project coordinated by the Deh Gah Gotine First Nation; a boating program for Tłįchǫ youth that teaches traditional knowledge and skills; and a hide tanning camp in Łutsel K’e. In addition to financial support, funded projects may also receive equipment, training, and program support. Quick Facts

Contacts Steve Ellis Northern Lead Tides Canada Email: [email protected] Jess Dunkin Director, On the Land Programs NWT Recreation and Parks Association Email: [email protected]  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the sixth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. If I were to make a word cloud of my interview with Erin Kelly (Environment and Natural Resources’ representative on the Collaborative), I suspect that collaboration, connection, and community would appear in bold, a reflection of her priorities as a scientist and as a public servant. Erin traces these priorities to her time as a graduate student at the University of Alberta: “I worked with David Schindler, a very applied scientist. Our involved communities in the Rockies and partnerships with other organizations like Parks Canada, so I learned a lot about working collaboratively. In my experience, meaningful partnerships, but particularly community involvement always makes things better.” Erin, who earned a doctorate in Environmental Biology and Ecology in 2007, joined the GNWT in 2010. Since then, she has served as a Water Specialist; the Manager of Watershed Programs & Partnerships; Assistant Deputy Minister for Environment and Natural Resources; and, most recently, as the Acting Deputy Minister for ENR. In those capacities, Erin has played a key role in a number of critical water and other environment-related initiatives. She worked on developing and implementing the Water Stewardship Strategy, she was a part of the negotiating team for the Transboundary Water Management Negotiations, and she led the development of the NWT Community-Based Water Quality Monitoring Program. Data from this program is publically available through Mackenzie Datastream, a collaboration between Erin and her team, Carolyn Dubois at the Gordon Foundation (another Collaborative member!), and others. In the almost two decades that she has been working in community-based science, Erin has had a lot of opportunities to speak with communities about what is important to them: “What I have heard time and again is that it all comes back to the experience of being on the land, but also ensuring that we provide opportunities for youth and elders to connect, so that there is a passing on of knowledge.” These kinds of conversations inform ENR programming, which includes long-standing youth programs like Tundra Science and Culture Camp and Take-a-Kid-Trapping. More recently, the department has been championing community-based monitoring and Guardian programs. Another thing that Erin heard repeatedly in conversations with community members was the importance of linking traditional knowledge and science. For this reason, she has worked hard at ENR to promote this kind of thinking and practice amongst her colleagues. (She suspects that this is why she was tapped by former Deputy Minister Ernie Campbell to represent the department on the Collaborative.) Erin is accustomed to being asked why ENR is part of the Collaborative. On the land programs are so often understood as being related to physical or cultural health, but Erin is clear that there are environmental outcomes as well: “Part of the healing work that on the land programs do is about being one with the environment.” Here, Erin acknowledges the impact of residential schools on this relationship and the need for reconciliation, “Land-based programs help give people back the bond that they have with the land and the water and the animals.” Repairing this relationship has important stewardship outcomes. Not to mention, to focus solely on environmental or health benefits ignores how all of these things are interconnected. As Erin notes, “You can’t really take apart the land, traditional economies, culture, and health. They are all inter-linked and inter-twined…On the land programming promotes holistic health: environmental health, including personal health, wildlife health, the health of water. Everything together.” There is also the fact that land-based programs, regardless of their intent, create opportunities for monitoring: “When people are out on the land, regardless of who they are, they will monitor the land in their own way.” Like other partners, ENR was attracted to the Collaborative because the department’s leadership recognized there are better ways to do things, particularly in relation to processes such as accessing funds. Erin explains, “We understand the challenges that people face as they have to apply to different funding pots to have enough money to do project work. We believe in the work that is being done on the land in the NWT, so anything that we can do to streamline that process and support people getting out on the land is something that is important to us.” ENR contributes to the Collaborative in a number of ways. Where possible they give funds, but they also provide in-kind support: “Because we have regional offices and also in some cases wildlife or other officers and staff in communities, there is a lot of in-kind support we can provide, both in terms of equipment and expertise.” Depending on the project, ENR might share equipment, such as sleighs, wall tents, and outdoor gear, or infrastructure, such as cabins. They can also provide expertise: “If groups want to spend time on the land and they want to talk about fish, forests, water, wildlife, protected areas, etc., we have people with those skillsets.” ENR has also provided staff time to the Collaborative. The Collaborative Administrator, Sarah True, is an ENR employee. We’ll be profiling Sarah in a future blog post. For now, know that, according to Erin, “Sarah is amazing and she’s doing really great work for the Collaborative.” Erin is happy with the early days of the Collaborative: “One of the real benefits for me of sitting at the table has been to learn what others are doing, to see how our mandates are interlinked, and to see how we can work together in other ways.” Like Steve Ellis, Erin sees unrealized potential in the relationships that different partners could develop. She also sees opportunities for ENR’s place in the Collaborative to evolve: “I don’t think ENR’s support is fully realized at this point. I think there are lots of possibilities for strategic partnerships between funded projects and ENR, both in terms of equipment and expertise.” Erin has always enjoyed being outdoors, but it was moving North that made her really understand the importance of being on the land to her wellbeing. No longer able to easily visit her family cottage, Erin realized how much she needed a space that was away from everyday life. She and her partner had the good fortune to find a cabin on River Lake. Accessible only by boat or snowmobile, Erin can pinpoint the place where she crosses over to “on the land mode”: “The stuff in town doesn’t disappear, but I don’t have to think about it while I’m there.” The North has also opened her up to other ways of being on the land: “I love the ability up here to learn from others who have different perspectives and do other things. For my 40th birthday, Fred Mandeville Jr. [ADM of Operations at ENR] took us to the East Arm and we just travelled around with him and his son. Learning from the master was amazing.” If Erin has her way, more people across the territory will have similar opportunities. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like GNWT Environment and Natural Resources to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the fifth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. In 2014, Steve Ellis, the recently appointed Northern Lead for Tides Canada, found himself with a bit of money for an on the land camp in the Dehcho. He quickly realized the money wouldn't go very far. At the same time, he was aware that his was not the only organization supporting land-based programs in the NWT, so Steve arranged a meeting with Debbie Delancey, Deputy Minister for Health and Social Services. At the time, her department was piloting land-based programs for wellness purposes. The gist of that meeting, to borrow from Steve, was: "I have some money, you have some money, there are other organizations supporting on the land programs. Maybe we should look at figuring out some way of pooling our resources and making our money work better for us and for the people doing this work on the ground." Debbie agreed. In the weeks that followed, Steve and Debbie reached out to Erin Kelly of Environment and Natural Resources, Kyla Kakfwi-Scott of Health and Social Services, and Rebecca Plotner of Dominion Diamond. The group envisioned a system in which a wide range of organizations could pool their resources, attract additional funding, reduce the administrative burden of people delivering land-based programs, and, most importantly, “empower Northerners to set priorities for how the pooled money should work.” Steve’s employer, Tides Canada, is a philanthropic organization that connects donors and doers to in the pursuit of “a healthy environment, social equity, and economic prosperity for all Canadians.” In recent years, they have put more of their energy into nurturing collaborative funds for just these reasons. A gathering of government, industry, NGOs, and philanthropic organizations later that year to learn more about collaborative funding models from those with experience in Manitoba, British Columbia, and Australia brought the idea one step closer to reality. In the fall of 2015, the NWT On The Land Collaborative was officially launched. In its first year, the Collaborative distributed $480,000 to 35 projects across the territory. At the outset, Steve’s self-described role was that of “catalyst or instigator, depending on your point of view.” He not only initiated the conversation with Debbie, but he and Tides Canada were integral to organizing the November 2014 gathering. As the Collaborative has developed a momentum of its own, Steve has been able to focus more on the responsibilities of a funding partner—securing funds from his organization and participating in the annual review and approval of applications—though he continues to play an important role attracting philanthropic foundations to the Collaborative and he does other administrative work besides. Tides Canada hosts some of the dollars that are part of the Collaborative’s funding pot. They also provide web space and communications support. Steve grew up in Winnipeg. It was while completing a Masters in Environmental Studies at Waterloo that he came north for the first time, to Łutsel K’e, a Denesoline community on the East Arm of Tu Nedhe (Great Slave Lake). Though he didn’t know it at the time, he and his wife Tracey would spend the better part of 15 years living in the community and raising a family. During that time, Steve worked for the Łutsel K’e Dene First Nation and other First Nations in the NWT and BC. Amongst other things, he delivered land-based programs: “I’ve been around long enough to have seen young people fifteen years later who have gone through these types of programs and who attribute change in their lives to these types of programs, so I am definitely a believer in these types of programs.” In 2013, Steve, Tracey, and their three kids moved to Yellowknife and Steve joined Tides Canada. Tides Canada, like Steve, sees on the land programs as vital to ensuring community wellbeing in the North: “Colonialism and trauma is largely responsible for the social issues in many Northern communities. Recovery from the harms of colonialism is about reclaiming what has been lost. On the land programs are great at rebuilding those relationships with community, culture, and the land.” For all of his experience with land-based programs, Steve too has benefitted from his involvement with the Collaborative: “We support a wide range of projects from the classic ‘community moves entire families out into the bush for a long time’ to urban disadvantaged youth spending an afternoon eating traditional food over a fire in a campground. We’re not in a position to judge what is more impactful. It’s depends on where people are and what their circumstances are. One thing I’ve learned through my participation in the Collaborative is that what an on the land program can be can be very, very different, but the outcomes are generally the same.” There is no doubt that the Collaborative had a successful first year. Funders, community advisors, and grant recipients have all been happy with the process. The only complaint is that the need far exceeds the current budget, so Steve’s goal over the coming months is to engage new donors and to encourage existing partners to devote more of their resources to the fund: “Most of the donors are still in the ‘let’s see where this goes’ mindset and I think it will be that way for a few years, but we would like to get to the point where people are comfortable enough with the collaborative approach that larger and larger amounts of the resources they have allocated for on the land programming can be run through the Collaborative.” Steve’s larger ambition is to make the Collaborative indispensable to land-based programming in the NWT. “We’ve wanted to be a one-stop shop and we are a one-stop shop, but I think becoming THE one-stop would be great.” In other words, the Collaborative would become the place to go for learning about innovative programs, best practices, and accessing tools to help with program delivery, as well as funding and resources. Steve also sees potential for the Collaborative to serve as a model for similar initiatives in the other territories. Steve, like other members of the Collaborative, enjoys spending time on the land himself. His Instagram feed of late has documented a hiking trip with Tracey and the kids to Utah and regular trips out to the family’s fish net on Yellowknife bay. Come summer, you are most likely to find the Ellis-Williams clan cruising around Tu Nedhe in a motor boat, with a requisite stop in Łutsel K’e, Steve’s first home in the North and one of the many places he has seen firsthand the value of land-based programming. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Tides Canada to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and annual funding decisions. This is the fourth in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Rebecca Plotner’s enthusiasm for the Collaborative is infectious: “I really think [the Collaborative] is wonderful…Everyone who is working on it is really great with many good ideas…And the programs being supported are awesome!” And she should know. Rebecca, who works for the Dominion Diamond Corporation, has been involved with the Collaborative since it was little more than an idea. She recalls early meetings with Kyla Kakfwi-Scott (GNWT Health and Social Services) and Steve Ellis (Tides Canada), two of the driving forces behind the Collaborative: “It started off with three or four of us hanging around a table talking about it, throwing out different ideas, and figuring out how we could get it expanded.” Even at that early stage, Rebecca saw the potential of bringing together diverse partners from government, industry, and the non-profit sector to pool their resources and support land-based programs in the territory: “We looked to examples in the south like the Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Fund. They started out with a small amount of money, but it keeps growing and they are able to help out so many people now.” Rebecca is equally impressed with how far the NWT On The Land Collaborative Fund has come in such a short period of time: “Seeing where it started to having our first workshop to where we are today in just over two years. It has been great to see the interest [in the Collaborative] and how much people have wanted to support it. The distance we covered in that time is huge!” Rebecca’s employer shares her enthusiasm for the Collaborative—they recently doubled their investment in the fund. In their words, Dominion Diamond is “pleased to be able to contribute to an initiative such as this, which emphasizes collaboration and partnership, enabling projects to come to a single place for funding. We believe the NWT On The Land Collaborative will be a key resource in the sustainability of on the land projects in the North.” Rebecca is a member of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation. Although born in Illinois, she was raised in Dettah by her parents Sarah (nee Charlo) and Mark Plotner. Her grandparents are Judy (nee Betsina) Charlo the late Joe Charlo. After studying Biochemistry at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, Rebecca returned to Yellowknife. In 2010, Rebecca was hired as a Community Relations Advisor Trainee with BHP Billiton. She was attracted to the people-oriented nature of the position (“I love talking and working with people!”) and the prospect of seeing more of the territory (“I grew up in the North, but I had never been to a community that you can’t drive to.”). Six-and-a-half years later, Rebecca is a Community Development Advisor with Dominion Diamond, which acquired BHP’s interests in 2013. Dominion operates the Ekati Diamond Mine, located on Lac de Gras approximately 300 kilometres northeast of Yellowknife. Amongst other things, Rebecca helps to administer the Ekati Plus Community Development Program. Through this program Dominion Diamond provides financial and in-kind support to innovative initiatives that have a long-lasting impact on the people and communities of the North, including on the land programs: “At the Ekati mine, we have long recognized the importance of on the land activities, Traditional Knowledge (TK), and providing opportunities for young people and other community members to learn from their Elders and each other.” The mining corporation’s funding priorities include traditional knowledge activities, youth education, literacy initiatives, and healthy lifestyles. Land-based programs have the potential to satisfy all of these objectives. Rebecca, for her part, values programs that support children and youth spending time on the land. Growing up in Dettah, Rebecca spent a lot of time outside: swimming at the docks, fishing on the big lake, and visiting her family’s cabin. Her mom was raised on the land in Wool Bay and she made it a priority to pass along her experiences and values to her kids: “We’ve always had that connection to the land and respect for the land. It’s always been a part of my life.” One of Rebecca’s favourite things now is to spend time at her family cabin, which is a 1.5 hour boat ride and 5km hike from Yellowknife. When she looks around Dettah today, she sees children and youth spending more time in the community and inside: “They’re not running around on the ice or going fishing on the back lakes as much. So, for me, it’s great to see programs that encourage them to get out on the land and connect them with our culture.” When asked about the future of the Collaborative, Rebecca responded without hesitation, “I know it’s going to expand…I’m really looking forward to seeing how far it goes…and the type of impact that it’s going to have in the North. It’s going to be great.” The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like Dominion Diamond to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and funding decisions. This is the third in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Carolyn DuBois, The Gordon Foundation’s representative on the Collaborative, is Toronto born and raised, but that doesn’t mean she’s out of place in the out of doors: “I love canoe tripping! Everyone is always surprised by this, maybe because I live in the city, but canoeing is my favourite!” Summers at Glen Bernard Camp and a high school semester at Outward Bound fostered this passion for paddling. These experiences also set her on career path that would see her focus on the human dimensions of water-related environmental issues. Following an undergraduate degree in Biology from Mount Allison, Carolyn packed her bags and headed for Barcelona where she completed a Masters in Environmental Management at the Autonomous University. Her research explored conflict between artisanal and industrial fisheries in Africa.. Today, Carolyn is the Water Program Manager at The Gordon Foundation, a philanthropic organization based in Toronto that seeks to amplify Northern voices and promote collaborative stewardship of freshwater resources. Amongst other things, Carolyn is responsible for the recently launched Mackenzie DataStream, an open access platform for sharing water data in the Mackenzie Basin. Mackenzie DataStream was built in close partnership with the government of the Northwest Territories. The project, which brings together information produced by community monitoring programs throughout the Basin, enables evidence-based water policy. As part of this project, Carolyn spent a few days on the Deh Cho (Mackenzie River) last year: “For much of my time at the Foundation, I’ve been managing the Mackenzie program, so to actually be on the river was really special.” The trip was also an opportunity to get to know the people and communities with whom she had been working for four years in a really different way: “Before this, I had spent a lot of time on the phone with people from Toronto. It’s very different to be out on the water with people, but also to have that time around the fire to really get to know people.” Learning trips are also an important part of how the Collaborative operates (learn more about our first learning trip here). The Gordon Foundation (previously the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation) is a new partner for the 2017 grant cycle. Founded in 1965, the Foundation is an operational charity, which is to say that they deliver their own programs, including the Jane Glassco Northern Fellowship, a policy and leadership development program for Northern youth. (Jane Glassco Fellow Kyla Kakfwi-Scott has been instrumental in the evolution of the Collaborative.) That said, the Foundation maintains an interest in supporting grassroots initiatives that further their mission. The Collaborative provides an opportunity for the Foundation to do just that, by connecting them with meaningful community-driven land-based projects in the NWT. The value of land-based programs for Northern communities is self-evident to the Foundation’s President and CEO Sherry Campbell. Since assuming that role early in 2016, Sherry has travelled extensively in the NWT and Nunavut. Regardless of the community or the issue being discussed—mental health, cultural revitalization, residential schools, sustainability—Sherry has observed that land-based programs are always part of generating solutions that promote community wellness: “We keep hearing over and over how important on the land programming is and we need to pay attention to that.” Before joining The Gordon Foundation, Sherry was the president of Frontier College, a national non-profit literacy organization. That experience made her sensitive to the onerous cycle of funding applications and reporting: “The capacity to write good applications and good reports can be a barrier…I saw solid community-led projects that were important to the community that were not getting funded because of the complexity of application processes. What I really love about [the Collaborative] is that it removes these barriers and focuses on getting good, community-led work done.” Sherry sees important lessons in the funding model adopted by the Collaborative. For example, she values the fact that the Collaborative provides more to communities and projects than funds. She also appreciates the Collaborative’s emphasis on providing continued support to projects that work: “Funders always want new and innovative projects, but if you really want to make change in communities, you also have to invest in and maintain what is working.” Of particular note is the Collaborative’s commitment to community-directed programming: “I like the fact that [the Collaborative] just gets out of the way. You give [communities] support, you help them get them what they need, and then you give them the funds that lets them do what they are good at doing.” The Collaborative, in other words, is supportive, but not meddlesome. Sherry attributes this approach to the people at the table, many of whom are community leaders themselves and thus are respectful of local goals and expertise. The Collaborative also benefits from having southern partners like The Gordon Foundation, who brings a network of foundations and organizations to the table and also a capacity to translate northern experiences for southern audiences. Carolyn, as the Foundation’s representative on the Collaborative, is enthusiastic about this new responsibility: “I’m really looking forward to seeing the breadth of work that people are doing and also the ideas that people are developing to address issues in their particular place.” She has seen firsthand how land-based programs are opportunities for learning, growth, and fostering well-being and she looks forward to finding ways to help NWT communities continue to offer such programs. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like The Gordon Foundation to support land-based initiatives in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]).  The NWT On The Land Collaborative Fund is a collective of partners from government, industry, philanthropy, and beyond, working together to support land-based programs and projects in the NWT. Each of these partner organizations has a representative that participates in quarterly meetings and funding decisions. This is the second in a series of profiles of the people and organizations that make the Collaborative possible. You can read the other profiles here. Steven Nitah’s resume is longer than your arm: trapper, recreation coordinator, guide, forest fire fighter, CBC television producer, community liaison officer, MLA, chief, CEO. These days, he is the Northwest Territories Advisor for the Indigenous Leadership Initiative (ILI), the Chief Negotiator for the Łutsel K’e Dene First Nation (LKDFN), and the head of Nitah & Associates, a consulting firm specializing in negotiation and communication. As if this wasn’t enough, he is also ILI’s representative in the NWT On The Land Collaborative Fund. Steven grew up on the East Arm of Great Slave Lake: “I was raised on the land with grandparents and great grandparents, in and around Łutsel K’e: south side, east side, north side, west side, depending on the season.” Although Steven occasionally attended the local school in Łutsel K’e, his true education came travelling and living on the land with the Elders: “The Elders I grew up with were never exposed to residential schools, were never exposed to the assimilationist policies of the Indian Act. They lived their lives as independent people, in harmony with their lands and they took care of each other…That’s shaped who I am.” Between 1999 and 2003, Steven served as the MLA for Tu Nedhe. In 2008, he was elected Chief of Łutsel K’e, a position he held for two years. While in that role, Steven formalized negotiations with the federal government on the creation of Thaidene Nëné (Land of Our Ancestors in Dënesųłiné), a park preserve covering more than 33,000 square kilometres of the East Arm and forests beyond. Steven continues to be involved in the process today as a negotiator for the band. Steven just celebrated his one-year anniversary with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative (ILI), a non-profit organization committed to “help strengthen Indigenous nationhood and fulfill Indigenous cultural responsibilities to the land.” ILI counts Stephen Kakfwi, Bev Sellars, and Ovide Mecredi amongst its Senior Advisors. In Steven’s own words, ILI is a “body that can help restore what was taken out of Indigenous communities and families through residential schools and assimilationist policies.” Central to restoring traditional forms of governance and social organization is “reconnecting with the land” because, as Steven notes, the land is and has always been “the basis of identity of Indigenous people.” To this end, ILI supports a variety of initiatives across the country related to governance and land use planning. At present, they are lobbying the federal government to fund a national network of Indigenous Guardian programs. Building on the success of programs in Australia and British Columbia, ILI is urging the federal government to invest $500 million over five years in a pilot project that would see Indigenous people across the country engaged in environmental monitoring and protection, stewardship, and emergency response in their traditional territories. Locally, ILI has worked with guardian programs in Łutsel K’e (Ni Hat’ni Dene) and the Dehcho (Dehcho K’ehodi). ILI also supported the Sahtúgot’ine Dene people of Délįne in their successful pursuit of self-government and the designation of the Great Bear Lake Watershed as a World Biosphere Reserve. When Steven started with ILI in 2015, it was a natural fit for him to represent the Initiative on the Collaborative. Steven is keenly aware of the value of land-based programs: “Land. It’s the land. It’s giving people an opportunity to get onto the land, giving kids and their families and opportunity to get back onto the land…as a group...to help promote the stories of the land, the understanding of those lands, and to transmit that knowledge to younger generations.” But sometimes, the work is easier said than done. As Chief of Łutsel K’e, Steven saw firsthand the time spent on funding applications and reporting: “It takes more energy than the program that you’re applying for funds for.” The Collaborative, by contrast, functions as a clearinghouse for funds, information, and resources. The intention is to remove some of the administrative burden from program coordinators and leaders so they can focus on getting people out on the land. Going forward, Steven would like to see more family-centred initiatives and programs that engage language speakers apply for the fund. Given his experiences growing up on the land and in his language, this makes sense, though he is quick to note that each community must identify what land-based initiatives are a good fit for them. These days, Steven divides his time between Łutsel K’e and Yellowknife, where two of his three kids are attending school. His responsibilities to his community and ILI mean he has less time now than he would like to spend on the land. When he is able to get away, he enjoys being out on Great Slave Lake with his kids, retracing the routes he travelled with his grandparents as a child: “Just being there…I can see my grandmother doing her thing. I can see my grandfather doing his carving, and the places that he hunted.” Revisiting old campsites and hunting grounds links Steven to his past and is part of preparing his children for their future. The NWT On The Land Collaborative depends on partners like the Indigenous Leadership Initiative to support land-based programs in the NWT. If your organization is interested in becoming a partner, please contact Steve Ellis ([email protected]). |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed